By Max Budovitch

This blog post is a result of a DRAN-sponsored summer internship with Habitat International Coalition (HIC) in Mexico City, Mexico.

Displacement is not new to residents in Mexico city. The 1985 earthquake displaced thousands of the capital’s most vulnerable residents. One of the most important outcomes of reconstruction following the earthquake was the formation of multiple housing rights movements that helped lay the groundwork for some of Mexico’s strongest anti-displacement and housing rights advocates.

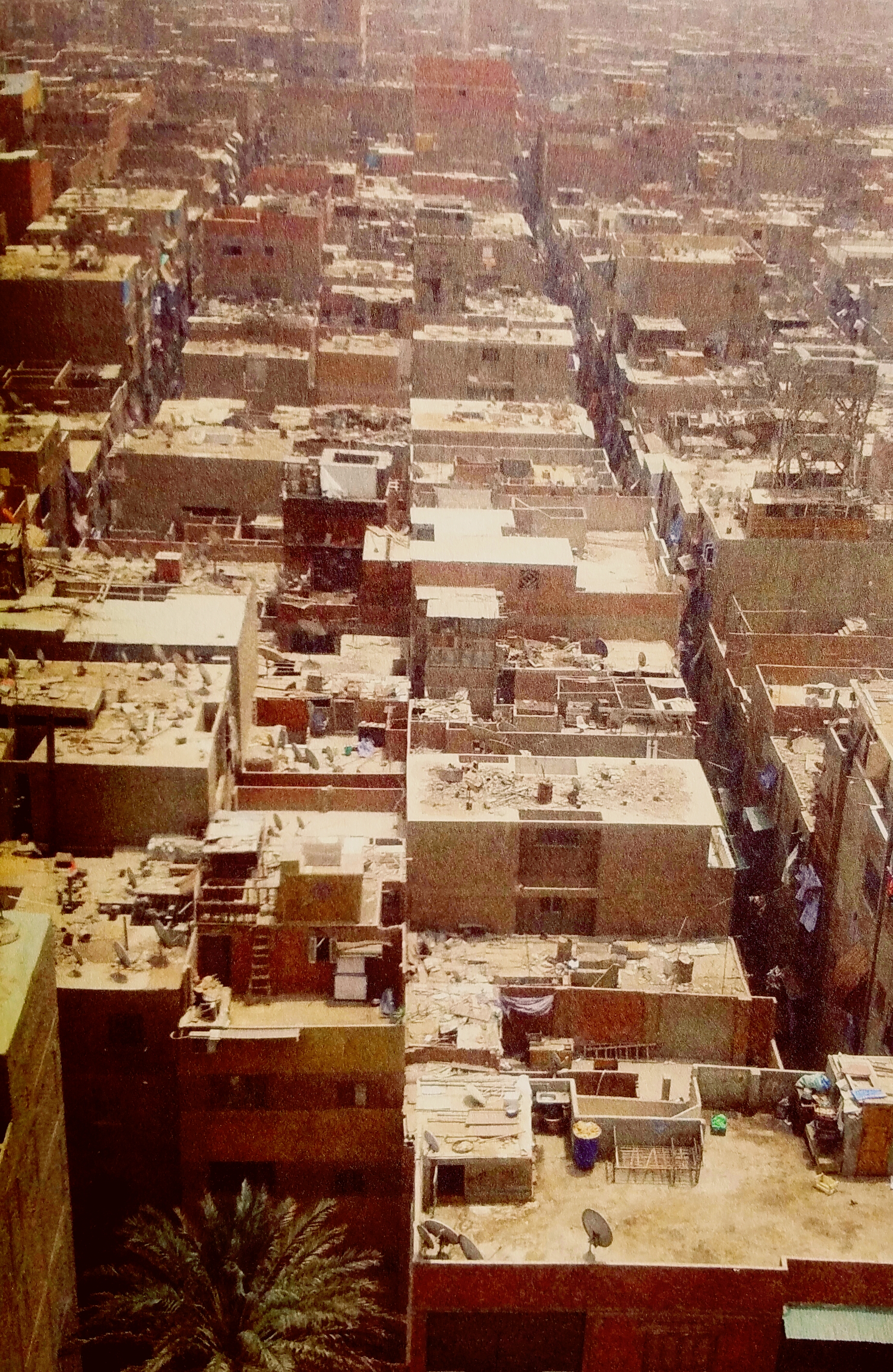

A typical semi-formal settlement on the urban periphery

The most recent wave of development-induced displacement in the capital dates to the liberalization of Mexico’s economy in the 1990s. This climate created a boom in the higher segments of the urban real estate market that has made it increasingly difficult for lower income households to live in the central areas of the capital. This general trend is punctuated and exemplified by specific initiatives such as the ‘revitalization’ of Mexico City’s Historic Center, the construction of high-rise office towers along the Paseo de la Reforma, and the commercial development of Santa Fe. Just as developer friendly public policy is contributing to this dynamic, so is the lack of regulation. As in most global urban cores, rampant real estate speculation is unfettered in Meico City. Public policy such as the initiative to formalize street vendors in the Historic Center and develop the area into an international tourist destination, as well as a public initiative to densify centrally located neighborhoods through developer incentives, have led to a consolidation of property interests in the hands of a number of wealthy developers and investors who target middle and high market segments while capturing public rents. This dynamic is one of the reasons why many middle and lower income tenants are evicted from their well-located dwellings and have no choice but to move to cheaper zones in the State of Mexico or the South Eastern outskirts of Mexico City where there is often a lack of basic services and where one might spend up to six hours commuting to and from work every day.

Windows are bricked over as tenants are evicted

During July and August 2017, I participated in a DRAN supported and organized internship at Habitat International Coalition’s Latin America offices based in Mexico City on the issue of displacement in the capital. Among several housing rights groups active in Mexico City including the Movimiento Urbano Popular (MUP) and the Unión Popular Revolucionaria Emiliano Zapata (UPREZ), I coordinated with a loosely organized coalition of residents in the city’s centrally located Colonia Juárez neighborhood, which has come under development pressures that has forced many residents to find more affordable housing elsewhere (pressures that the local community understands to be part and parcel of a wave of gentrification). I gathered testimony and experiences of eviction and displacement from residents during community meetings and created a work plan with the residents to write an anti-displacement manual. When completed, the manual will be a condensed source of useful popular and legal terminology, symptoms of displacement pressures, and a matrix of possible responses and counter-measures that residents can use to mobilize in defense of their communities. The reality of home invasions and occupations by strongmen, new property owners changing the locks while tenants are at work, and the legal and practical challenges of holding owners and developers accountable in court inspired the community to envision a manual that would offer advice to residents on how to unite and combat threats of eviction before it becomes too late.

A community meeting

I also worked with the community in Colonia Juárez to draft a locally-tailored version of the Housing and Land Rights Network’s Displacement Impact Assessment Survey. The Survey, previously known as the Eviction Impact Assessment tool (EvIA), is a methodology based in the UN Basic Principles + Guidelines on Development Based Evictions and Displacement, which was initially developed by the Housing and Land Rights Network and is currently being adapted and applied by DRAN to different displacement scenarios. Adjusting the Survey for an urban context of development-induced displacement presented challenges such as how to measure the impacts of both the threat of eviction and eviction itself on heterogenous urban households that, while residing in the same neighborhood or even within the same building, might face very different types of eviction threats and possible outcomes.

The manual is envisioned as a living document which can adapt to the constantly changing threats faced by housing rights and advocacy groups in Mexico City. One potential adaptation is to include feedback from Displacement Impact Assessment surveying as different communities use this methodology to measure the impacts of displacement. Moreover, the response to the September 19 earthquake this year has ushered in a wave of building demolitions and relocations under the pretense of seismic risk. Some of these demolitions are reportedly conducted without proper investigation and without informing residents.[1] A rights-based approach to housing for those displaced by the earthquake as well as stronger protections against development-related evictions can help ensure greater access to housing for those affected. The evolving crisis, and human rights violations as a result of multiple causes of displacement is a critical issue that the manual might be able to engage.

[1] Author’s telephone interview with freelance journalist living in Colonia Roma, D.F. October 1, 2017.; National Public Radio. “Quick Building Demolitions Rasie Questions in Mexico”. September 28, 2017. <http://www.npr.org/2017/09/28/554331332/quick-building-demolitions-raise-questions-in-mexico>